ON the 14th anniversary of independence, South Sudan teeters on the edge as the 2018 peace accord collapses under fresh fighting, political purges, and ethnic tension.

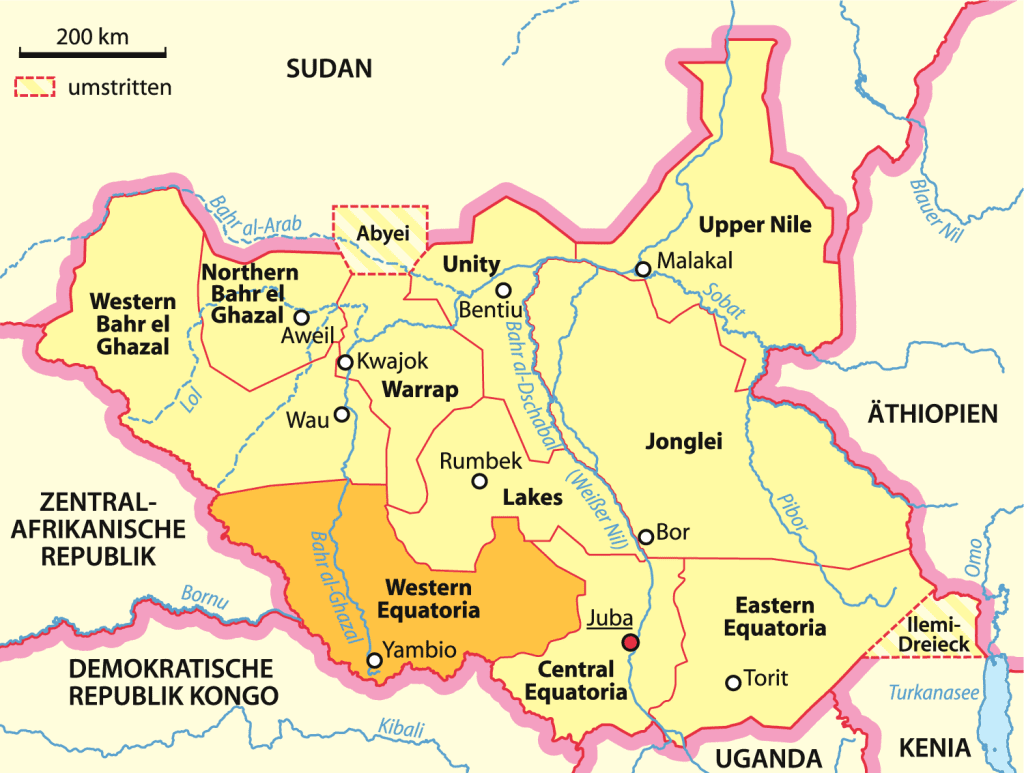

Fourteen years after it raised its flag as the world’s newest country, South Sudan is adrift. The hopes for peace, unity, and stability have all but collapsed. On July 9, 2025, while officials delivered ceremonial speeches in Juba, renewed fighting in Western Equatoria State told a grimmer story—a peace deal gasping its last breath, and a country lurching back towards the abyss.

The 2018 Revitalised Agreement for the Resolution of Conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS) was once hailed as the last real shot at ending the cycles of violence that erupted after the country’s first civil war in 2013. But now, that deal is all but dead—its body cold, though few, including the United Nations, are willing to say it plainly.

Clashes between government troops and opposition fighters in Western Equatoria—especially in Mundri East and Tombura counties—are no longer scattered skirmishes. They are signs of a peace that has unravelled and a state that is barely holding together.

Machar Sidelined, Opposition Fractured

In June, reports surfaced of a large deployment of government forces to Mundri West, suggesting preparations for an offensive against areas controlled by the National Salvation Front faction led by Gen. Thomas Cirillo (NAS-TC), and the Sudan People’s Liberation Army-In Opposition (SPLA-IO).

The troop movements followed Vice President Dr Benjamin Bol Mel’s declaration that the government would reclaim control of places like Kediba, a longtime SPLA-IO stronghold. The statement mattered—especially since SPLA-IO leader and First Vice President, Dr Riek Machar, is effectively under house arrest in Juba.

But the offensive is only part of the story. In what many see as a direct sabotage of the peace agreement, President Salva Kiir recently removed two governors—those of Upper Nile and Western Equatoria—positions allocated to SPLA-IO under the power-sharing deal. He replaced them with loyalists from his own party, openly breaching the agreement. At the same time, the government is backing Stephen Par Kuol, a former Minister of Peacebuilding, who now claims leadership of the SPLA-IO in place of Machar.

There are now persistent, though unconfirmed, reports that NAS-TC and SPLA-IO have joined forces to create a new formation—the Equatoria Defence Forces (EDF). If verified, this would mark a serious and dangerous shift. It would be the first time historically separate armed movements in Equatoria have come together under one command.

Among Equatorians, recent events are being read as a declaration of political war. The dismissal of their most senior official in government, former Vice President Dr James Wani Igga, has deepened that view. Igga, who hails from Western Equatoria, was replaced by Dr Bol Mel, a Dinka from Northern Bahr el Ghazal. The reshuffle has stirred old grievances about ethnic exclusion and Dinka dominance in government.

Sources on the ground say both NAS-TC and SPLA-IO have boosted their troop presence in the region and are preparing for confrontation. Fear hangs thick in the air. Residents in Mundri East are fleeing into the bush, anticipating what could come. Once known as the “Green State” for its relative calm, Western Equatoria is now on edge—yet another front in a widening storm.

Broken Systems and a Dying Economy

The peace deal was supposed to prevent this. It promised to end exclusion, reform the military, and produce a new constitution. But from the beginning, R-ARCSS was undermined by mistrust, foot-dragging, and political scheming. Kiir and Machar, the two main players, never treated it as a nation-building tool. Instead, it became a truce between rival camps, dressed up as a national roadmap.

Now the cracks are gaping. The ceasefire monitoring body with a mouthful of a name, Ceasefire and Transitional Security Arrangements Monitoring Mechanism (CTSAMM), is toothless. The promised unification of government and opposition forces has ground to a halt. Kiir’s administration is resorting increasingly to force. And outside the peace framework, groups like NAS-TC, who rejected the deal from the start, are stepping into the void left by a retreating state.

Meanwhile, the country’s economy has fallen apart. Oil—the backbone of South Sudan’s finances—is producing less revenue due to constant conflict and decaying infrastructure. Food insecurity is severe: over 7 million South Sudanese—more than half the population—are going hungry this year. Famine is no longer a threat on the horizon. It is a real and growing danger.

The World Is Moving On

More than 4 million people have been displaced, scattered across South Sudan or stuck in refugee camps beyond its borders. The failure to bring together the country’s armed factions into one national army has left a patchwork of militias, most loyal not to South Sudan but to the men who control them.

Once heavily involved, the international community has largely withdrawn. The regional peace guarantors—Uganda and Sudan—are compromised or distracted by their own problems. Kampala has thrown its weight behind Kiir, even sending troops to confront Machar-aligned groups. Khartoum, locked in its own devastating war, is in no position to help.

IGAD and the African Union, who helped broker the peace deal, have fallen conspicuously silent. The UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS), tasked with protecting civilians, is still there—but constrained, reactive, and often sidelined politically.

In Juba, most people have stopped pretending. “We’re going to have a third war. A big, bloody one. Only this time, let it end properly—with a winner and peace,” a local transporter said. That kind of grim realism is spreading.

A new war in Western Equatoria would not stay contained. It could easily spill into Upper Nile and Jonglei—regions already volatile and heavily armed. Ethnic polarisation—between the Dinka-dominated government and non-Dinka rebel groups—would harden. The last civil war, between 2013 and 2018, killed nearly 400,000 people. The next one could be worse.

Pulling Back from the Brink

To stop that, urgent steps are needed. In flashpoints like Mundri and Tombura, local leaders must prioritise protecting civilians—not choosing sides. At the national level, there must be a reckoning. Riek Machar’s house arrest needs to end. The army must be unified—not in theory but in practice. The parties must return to the table—with new facilitators if necessary—and rework the political settlement before the entire project collapses.

The role of peace guarantors also needs rethinking. Uganda cannot be both referee and player. Sudan, for now, is out of the game. UNMISS must increase its patrols and strengthen its civilian protection strategy, especially in hotspots like Mundri East.

At the same time, humanitarian groups must brace for another wave of displacement. People are already on the move. Food, water, shelter, and safety will be needed immediately. The more resilient these communities become, the harder it will be for them to be drawn into the next phase of war.

Fourteen years ago, South Sudan promised a clean break from its past—a fresh start free from the horrors of war and political betrayal. Today, that promise lies in ruins. The peace deal, once a beacon of hope, is now clinically dead. Its collapse is written in the fear, silence, and bloodshed spreading across Western Equatoria.