Africa’s mounting debt crisis exposes a troubling paradox: a continent endowed with vast natural wealth, yet weighed down by rising liabilities, infrastructure gaps, persistent poverty, weak institutions, and stalled development. From Ghana’s prolonged debt crisis to Nigeria’s ballooning liabilities—where debt servicing consumes 75% of revenue alongside an additional $24.14 billion in external borrowing—the pattern is similar: borrowing without transformation.

The trajectory of Africa’s giants (Nigeria, Ghana, and Egypt) contrasts sharply with that of Rwanda which, despite its vulnerabilities, has deployed debt more strategically, and with Asian success stories (South Korea, Singapore, and China), where disciplined investment transformed debt liabilities into engines of growth. Rwanda’s debt-to-GDP ratio rose from about 20% in 2010 to over 80% in 2025, triggering a Fitch downgrade. Yet unlike Nigeria, much of Rwanda’s borrowing has been channelled into infrastructure, health, and technology, underpinned by long-term national planning and relatively strong governance. The contrast is therefore stark: while Africa’s giants struggle with rising debt and limited returns, Rwanda and Asia’s success stories demonstrate that, under the right conditions, borrowing can be turned into a driver of growth.

The central question for Africa is no longer whether to borrow, but why decades of debt have failed to deliver sustained prosperity, and what lessons can be drawn to reshape the continent’s path trajectory proportionate to productivity.

Public debt vs Growth productivity: Africa vs Asia

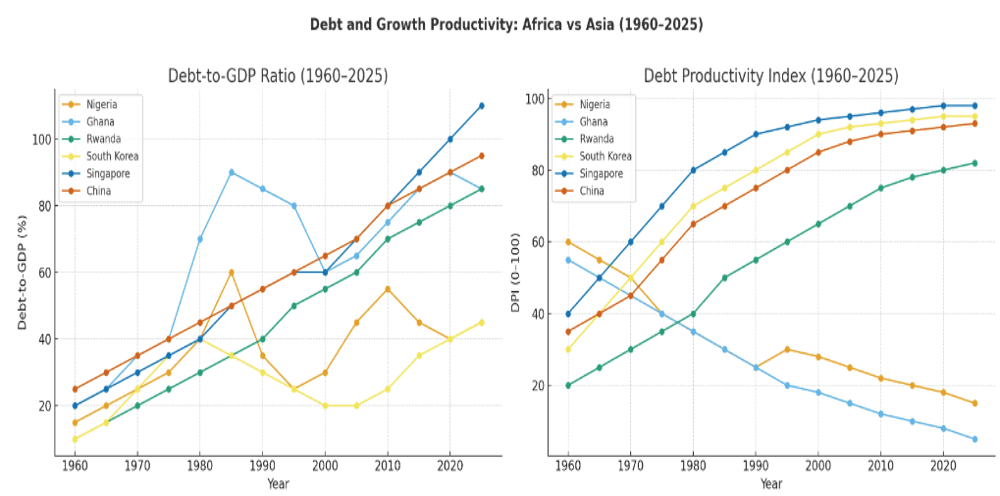

The “Debt Productivity Index” (DPI), an analytical construct derived from official debt-to-GDP ratios and GDP per capita growth, captures the correlation between rising debt and productivity. Figure 1 provides a counter-narrative for African and Asian countries.

Nigeria’s debt-to-GDP ratio rose steadily from the 1960s, reaching 39.1% in 1989 and 56.6% in 1990. It declined in Q1 2025 after GDP rebasing reduced the ratio to 39.4%. In contrast, Nigeria’s Debt Productivity Index (DPI) has shown a consistent decline. This trend was mirrored in Ghana despite Ghana’s debt-to-GDP peaking above 80% in the mid-2010s and again in 2023–2024.

Unlike Nigeria and Ghana, Rwanda’s rise in debt-to-GDP corresponds with a positive increase in its DPI. Rwanda’s positive DPI reflects patterns observed in South Korea, Singapore, and China.

Africa’s debt landscape

Over the past 15 years, Africa’s debt has surged, exposing countries to both domestic and global vulnerabilities. According to the IMF and World Bank, the median debt-to-GDP ratio in Sub-Saharan Africa reached 60% in 2025, almost double the level of around 30% in 2010. Nigeria’s debt-to-GDP ratio of 45% in 2025 sits below the continental average, while Ghana’s exceeded 80% by the time of its recent restructuring. Sudan, meanwhile, has remained in chronic debt distress since the 1990s, unable to regain international creditworthiness.

Another striking feature of Africa’s debt structure is its growing dependence on external borrowing, especially Eurobonds and bilateral loans from China. Domestic debt markets remain shallow, constrained by weak savings and fragile financial systems. Compounding these vulnerabilities are global shocks, commodity price volatility, and successive interest rate hikes, pushing many African countries into unsustainable debt-servicing positions.

The debt paradox in Africa: Rwanda as an outlier

The continent’s debt paradox manifests in multiple ways. Africa is rich in resources but poor in prosperity. It attracts vast financial inflows yet remains fiscally distressed amidst massive debt overhang. It holds immense energy and food potential yet struggles with power shortages and food insecurity. These contradictions are compounded by existing liabilities, high borrowing costs, volatile commodity markets, weak domestic revenue mobilization, and inability to curb illicit financial flight exceeding 89 billion annually. The consequences are unambiguous. Debt servicing diverts funds from health, education, and infrastructure, undermines human capital, deters investment, and increases borrowing costs for governments.

Notwithstanding this paradox, Rwanda stands as an outlier. Its long-term national plans, such as Vision 2050, coupled with investments in productivity-enhancing projects (transport infrastructure, ICT, and health systems), together with relatively stronger governance and donors and multilaterals alignments have rationalised its debt-to-GDP ratio climbing to over 80% in 2025. While Rwanda’s updated debt sustainability is not without risk, it implies that even high debt can underpin transformation if well managed.

Africa vs. Asia: What went wrong?

Like Africa, Asian economies once faced savings gaps forcing reliance on external borrowing. The so-called Korea’s economic miracle of 1962–1989 was an outcome of South Korea’s heavy borrowings in the 1960’ tied to an industrial policy to fund industrialization, mass education, and export-oriented manufacturing that produced globally competitive firms (Samsung and Hyundai). Between 1970 and 1990, Singapore’s state-led borrowing funded economic growth by building world-class ports, logistics, and human capital. Its disciplined fiscal planning and strict anti-corruption framework ensured high returns on public investment. China’s 1978 reforms leveraged borrowings to finance infrastructure, manufacturing, and technology, and lifting over 800 million people out of poverty. The common denominators in these debt successes are long-term planning, political and institutional discipline, knotting debt with industrial policies and export orientation, and employment of debt a strategic development tool.

So, while South Korea, China, Singapore, and Rwanda have witnessed a positive correlation between debt and increased productivity, many African countries have experienced the opposite. Africa’s borrowing has often been reactive, fragmented, and consumption-driven, routinely applied to politically motivated projects rather than economic productivity multipliers. Weak institutions, corruption, and debt overhang crowd out the fiscal space, leaving governments trapped in cycles of refinancing without growth.

Lessons for Nigeria and Africa

Unless debt reforms go beyond restructuring, Africa risks perpetual fiscal fragility. Further critical reforms include fiscal discipline and transparency, alignment of debt to credible development strategies and national priorities.

Secondly, domestic revenue mobilization is essential. Tax reforms can reduce dependence on external borrowing even as scepticism surrounding the implementation of Nigeria’s 2025 tax reforms continues to fuel non-compliance amidst public distrust. Trust is critical to long-term fiscal sustainability.

Thirdly, debts should be invested in growth-enhancing projects and tied to measurable growth multipliers alongside adequate medium and long-term economic planning. Debt-financed projects must generate returns that ease debt servicing.

Fourthly, deliberate strengthening of institutions is vital to eliminating inefficiencies and inconsistent borrowing policies.

Fifthly, governance and accountability mechanisms indispensable in preventing destructive and misuse of debts ought to be enforced to enhance high returns on public investment.

Finally, debt must be deployed as a premeditated development tool, rather than a reactive mechanism for deficit financing.

Unproductive debt must not define Africa’s destiny. The experiences of Rwanda, South Korea, Singapore, and China demonstrate that, when anchored in discipline, vision, and strong institutions, debt can fuel transformation. For Nigeria and its African peers, the debt paradox is not merely a fiscal dilemma but a systemic barrier to progress. The task is clear: close governance, trust, and strategy gaps; and turn liabilities into productivity, inclusive growth, and a foundation for lasting prosperity.